Members of Congress today may be more concerned about their messaging success than their legislative success. As former Senate Finance Committee chairman Sen. Max Baucus (D-MT) once said, “We’re all frustrated. We all wish there was more legislating and less messaging.”

Since former President Trump left office, the Republican party has struggled to find its image in a Biden presidency. One of the many freshmen in Congress who continue to support Trump is Rep. Madison Cawthorn (R-NC), by going on air at cable news shows, conservative podcasts, and expressing his thoughts through Twitter.

In late January, TIME writer Abby Vesoulis explained how Cawthorn approached his new job, noting that reliance on messaging was key to be successful. Instead of working to pass new legislation, Cawthorn made sure his office solely focused on communications, and there is a good reason why he chose that route to manage his office.

Because the Republican party is unable to pass legislation, and have legislative victories (such as the past 2017 tax reform bill), the party relies on messaging opportunities to gain grassroots support, which means more hiring opportunities for congressional communications staff.

Distinguished Princeton University political science professor Frances E. Lee dedicates an entire chapter titled “The Institutionalization of Partisan Communications” in her Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign, mentions how congressional parties craft messaging tactics over the years to compete for majority control of a governmental institution.

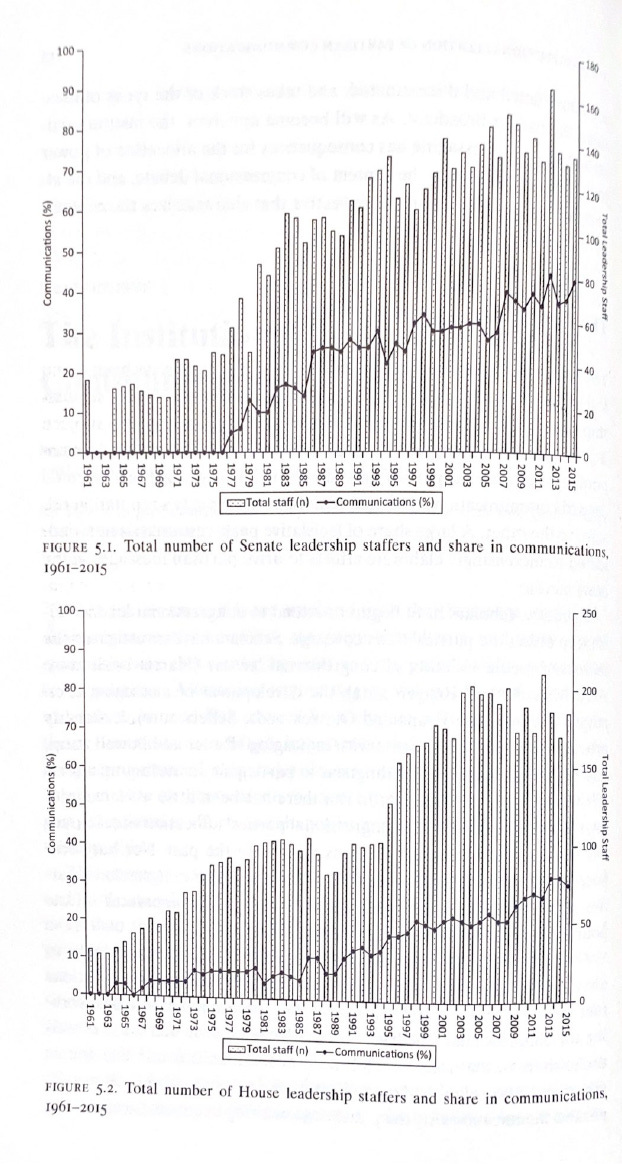

Congressional staffers who work in communications play partisan politics from the very start. In summary, Lee explained how communications positions have risen amongst staff in congressional leadership positions, stating in the year 1975, there were only 6 press aides who worked for congressional leadership. Later that number extended just below 10% into the early 1990s. In ten years between 1989 through 1999, more staff in leadership doubled, while the share of working in communications tripled. What used to be a quarter of all leadership aides working in comms later grew to 30% by 2013.1

Lee states various quotes from staff that provide sources regarding the role of communications personnel, one of which states that a member of Congress should be earning media coverage. This allows a member not to react to questions from the press because that member is setting the agenda, and having the press talk about issues that the member wants to be discussed. In other words, using messaging tactics may shape the public’s views on the issues, and the party altogether.2

She also explains policy staff is prone to frustration when the party’s overall message strategy will not allow credit claiming for compromises, because this will favor the looks of the party in the minority for negotiating successful legislation.

As one senior aide put it:

“You can’t say nice things about a bill you’re going to oppose. So even if your policy person got some good things in the Medicare prescription drug bill, you can’t get credit for it. If you’re opposed to the bill, you’re opposed to it. You can’t message that there are forty-five bad things in the bill, but a couple of good things, too. You can’t get credit for some little part of it.”3

Lee goes on to say the work of messaging is at odds with public policy because there has been friction going on between communications staff and policy staff in the offices inside Capitol Hill. Not only do staff in communications share a larger portion that makes up congressional staff, but they seem to become more important in the staff bubble, and climb the ranks of the hierarchy. Needless to say, communicators are more powerful today than they used to be decades ago.4

When parties are using communication advantages necessary to gain majority control of a governmental chamber, the more likely there will be an increase for more partisan communication. A source who served in the House told Lee, “There’s no actual debate. The quality of debate has changed when members aren’t engaging each other. The floor has become a campaign stage.”5

The goal of being a member of Congress is to be a legislator that participates in debates with colleagues who have opposing views and find ways to implement legislation on a bipartisan basis. Getting caught up in the egocentric field of communications will only hurt the fundamentals of being a legislator in the first place.

In conclusion, look no further than historian David McCullough’s quote from Ken Burns’s 1988 documentary film America: The Congress -

“In the old House of Representatives, which is now Statuary Hall, the members of the House looked up at two statues, which are still there. One is a figure representing liberty, and the other, behind them was Clio, the muse of history, keeping note of their actions and holding the clock - a very important idea, that what they did there didn’t just matter at the moment, but for time to come, that they would be measured by history, and that they had to live up to standards that would be set by historical precedent. Well, you know what they now look up to in the present day House of Representatives - the television cameras.”

Frances E Lee, Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (Chicago University Press, 2016), 114-115.

Lee, Insecure Majorities, 127.

Ibid., 130.

Ibid., 131.

Ibid., 139.